Phumani is aged and has trouble with her memory. “I can’t remember much about my childhood work,” she says, struggling to make herself comfortable in her plastic chair “but I started transplanting when I was about this high.” Her hand hovers less than 4 feet above the floor and a hushed amusement ripples through the assembled group. She is clearly loved and cared for by the community of rice growers we’ve come to talk with. But there’s no escaping the tragically comical fact that Phumani, at the age of 78, still stands at less than 4 feet high. Or, more accurately, stands less than 4 feet high again.

Phumani is crippled as a result of years bent over in rice fields.

Phumani can no longer stand up straight. Her body is bent double, her skeleton frozen into a permanent transplanter’s pose.

She goes on to describe how as a young girl, she would also have to help graze the cattle and do other household chores, help with the harvest and so on. Transplanting would start at 8 or 9am and continue until 4pm. “When I was young I felt no pain but then, later on, whenever I used to go for transplanting I really felt the pain in my hands and other parts of my body.”

Now, she is permanently racked with pain. But her story and her plight are by no means unique. You could walk into any rice-growing village in India and it is likely that at least one elderly lady will be crippled in this way. And such issues are not restricted to India.

Approximately one billion people grow rice in south and southeast Asia, more than half of whom are women. The majority suffer pain as a result of uprooting and carrying heavy seedlings and bending to transplant and to weed for days on end. The division of labour across most cultures and societies is such that women carry out most of this work.

Sabarmatee, an Indian researcher looking into the gendered impacts of the division of labour in rice growing in India has documented the hours rice farmers spend working, while also recording the weights carried, variations in environmental and ecological conditions and the physical, nutritional and psychological impacts of this work. “I found that, in conventional rice-growing, a woman will typically spend an average of around 150 hours for transplantation, another 150 hours for weeding, and another 150 hours for the removal of seedlings and transplanting per acre. So altogether, that comes to 450-500 hours per acre, which is 1,000-1,500 hours for 1 hectare. So, it’s a huge amount of time.”

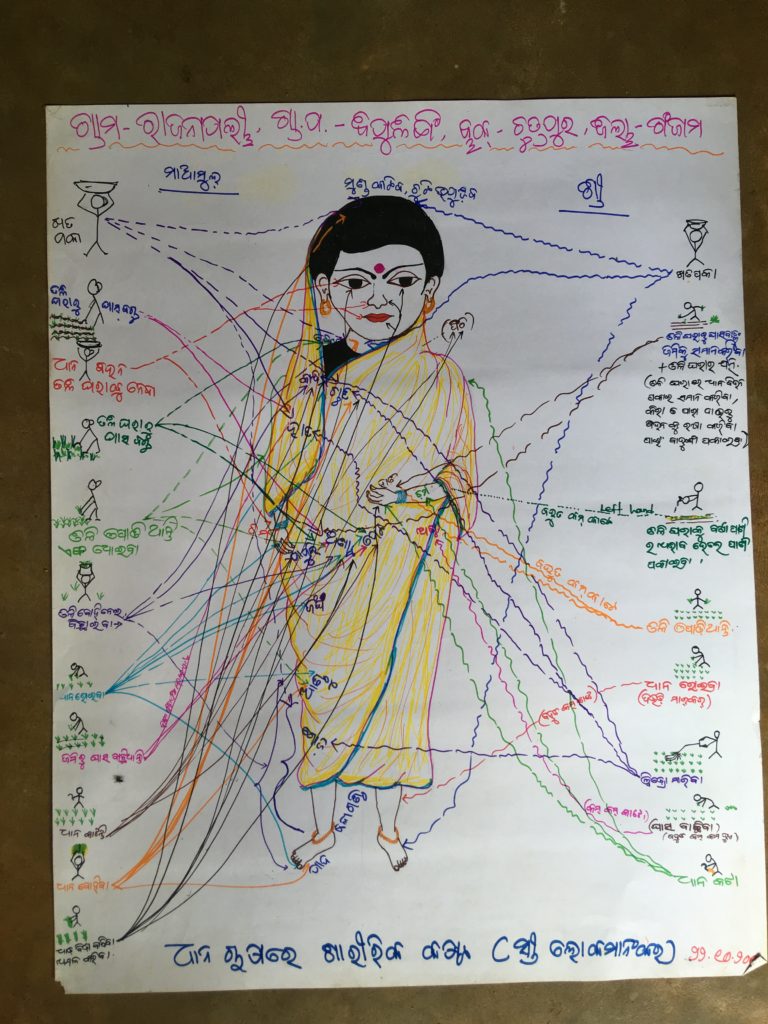

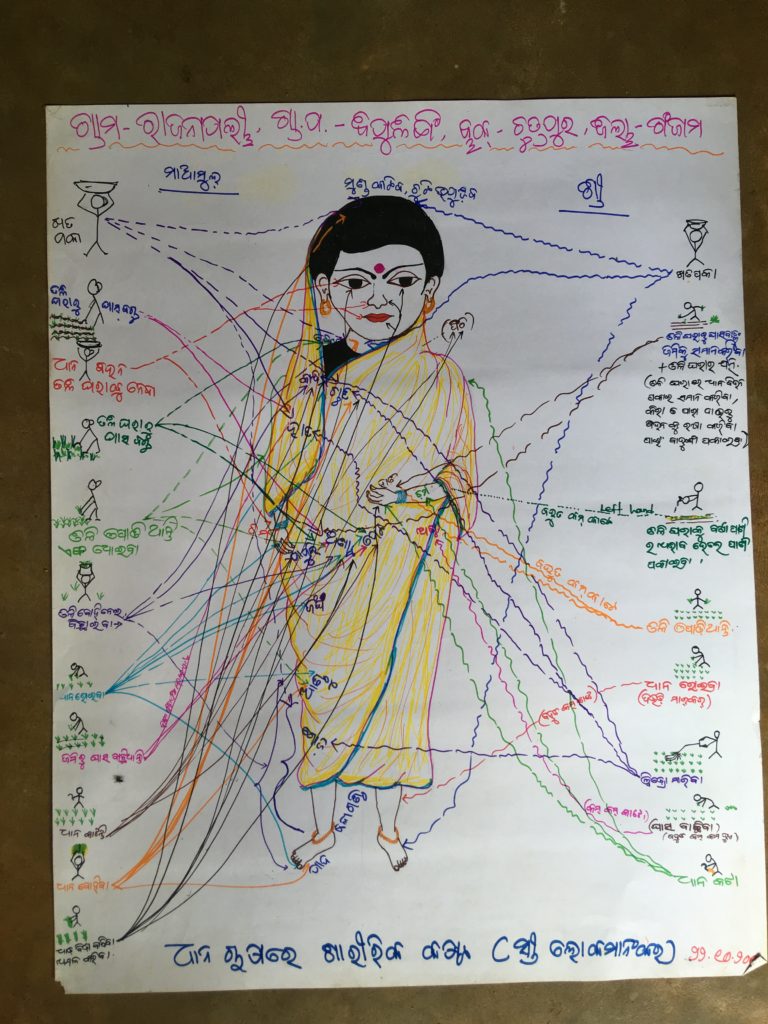

Sabarmatee’s RaCoPA method helps to visualise where women rice growers feel pain and how much.

As part of her research, Sabarmatee has devised a way of recording where women rice-growers feel pain and to what extent. She calls this Rapid Comparative Pain Analysis (RaCoPA) and it involves women drawing lines on a picture to show where they feel pain, in relation to specific rice growing tasks. “They were quite excited about it,” comments Sabarmatee when she describes starting out on her research. “They said: ‘you know, no-one ever asked us about these questions!’” But once she asked the question: “do you feel pain after working in the fields and if so, where?”, she found there was a consistency in the responses.

SRI4Women wondered if there would be a similar response in other countries.

After meeting Dokkeo Sayamoungkhoun, who grows rice near the village of Houaymalay in Khammouan Province, Laos, we asked her whether she felt pain related to her work: “I feel back pain mostly,” she replied, “when bending over and uprooting [seedlings].” We then asked her to discuss this issue with fellow villagers through a rudimentary RaCoPA exercise. The group of six women all agreed that uprooting, transplanting and weeding cause back pain. “I have bad pain in my back, I’m sore in my lower back and in my shoulders for many days” said one contributor. And the others agreed, adding that they particularly endure pain in their neck, especially when carrying seedlings from the nursery to the field and also sore hands and feet because they spend weeks on end working in flooded paddy fields under heavy seasonal rains. Often, that water is also contaminated with chemical fertilisers and parasites, which cause infections.

We have continued to ask rice farmers about the physical pain they typically endure in their work. Boleren Kujur of Gidhpahadi village, Sundargarh district, Orissa, told us that she and her fellow rice farmers have to transplant ‘constantly’. “After transplanting, we feel the pain” she said. And Felicita Topno, of nearby Brahamonomora village added that weeding has a similar effect: “Women are bent over weeding for 8 hours a day.” Hilrey Minz of Dhabadoli village agreed “We bend our backs like monkeys.”

However, Sabarmatee points out that these physical impacts have further consequences which are compounded by the farmers’ working conditions. “At that time, they don’t eat for long periods of time. So that also creates a problem for them. And I found it’s a time when most people are diseased. Like, malaria, typhoid, all sorts of waterborne diseases are there at that time and because of the wet environment, they get serial infections like candidiasis, tinea. So, they are diseased – cold, fever, coughing, those kinds of things.

“Whatever little money they have, they prefer to spend not on the food, but on labour and inputs. And health really takes a lot of money from their pocket – and that’s a time also for the school and college opening. So, they have to buy things for their children to send them to school and college.

“All these things demand hard cash and cash is very much constrained at that time. And whatever little they buy from the market, they give the majority of that to the menfolk, to the children and whatever is left – or not – they eat that.”

Sabarmatee’s findings provide a considered understanding of the socio-economic reality that millions of women rice farmers across the world face. Unfortunately, this is a reality that governments and development agencies have long overlooked.

The System of Rice Intensification (SRI) provides an alternative way of growing rice that can reduce and even entirely eliminate many of these problems.

How?

Rice-growing traditions vary from region to region. However, rice is typically transplanted when seedlings are 30-45 days old in tightly planted clumps and in fields that are permanently flooded. In many areas, chemical fertilisation has become the norm. In contrast, SRI requires the transplanting of very young 8-12-day old seedlings singly and at wide, regular spaces. The younger seedlings adapt more quickly to their new environment and have the space to establish a strong root system that supports a bigger stronger plant.

As a consequence, SRI typically results in higher yields at lower costs: as much as 90% less seed is required which means that women have to carry 90% fewer seedlings to their fields and as they are much younger they weigh a lot less too. Also under ideal SRI conditions fields are drained, which eliminates the effects of water-borne disease.

Through her research Sabarmatee has come to realise that the priorities of development agencies do not always correspond with the priorities of the farmers that they are obliged to represent.

Women carry seedlings that are 30-45 days old. Each bundle ways an average of 1.5 kgs.

“When the performance of a particular technology is discussed,” says Sabarmatee, “people narrow down their focus on yield and cost.” However, she argues, the importance and the impact of SRI goes far beyond the simple economic factors that are usually considered in assessing a technology. The reduced weight of the younger seedlings is literally a reduced burden on women who would typically carry around 24 bundles at a time, that she calculated weigh an average of 1.5 kgs each. Furthermore, the reduction in the number of seedlings transplanted under SRI reduces the amount of time spent bent over and frees up time for the cultivation of other nutritious crops or even time for the family. “It was very interesting,” recounts Sabarmatee, “I was living with a tribal family. I called the landlady ‘sister-in-law’. And in the middle of the day, I saw her nicely combing her hair, nicely sitting on the veranda. And then I said: ‘see? How can you afford to do this at this time of the day – are you not transplanting today?’ And she so happily said that: ‘you know, I have a lot of time today to rest, because I finished my SRI field!’ It means they really do the work in less time and in SRI you don’t have very flooded conditions and you don’t have to be inside the field for a longer time.”

The widely spaced seedlings under SRI have not only been proven to produce bigger, stronger plants that produce more and better-quality grain, but that space allows for the use of a mechanical weeder, sometimes a cono-weeder which is one item of investment that SRI calls out for.

“Under SRI, it has become easier to use the cono-weeder in between the lines,” says Felicita Topno. “We observed that after weeding like that and loosening the soil, more and more panicles would grow and the soil became more fertile and it isn’t such hard work. Now we can weed standing up like a human being.”

In Houaymalay, on the day that women rice farmers first tried transplanting according to the SRI methodology, Dokkeo asked the group: “So, would you say rice-growing is hard work?” “Not if it’s like today!!” replied one of her friends smiling.

The higher yields and lower costs which SRI brings have now been documented across at least 60 countries and their results have appeared in numerous peer-reviewed journal articles. This supports the suggestion that there is a legitimate economic argument for supporting SRI. However, SRI must be supported for other reasons also, reasons which directly relate to the physical well-being of the farmers who grow rice. SRI is a means by which to significantly reduce the occupational health impacts of traditional rice growing on women’s bodies. Women growing rice today do not need to end up like Phumani who has been transplanting since she was less than four feet high.

Watch the video

Phumani and her fellow villagers work with the Center for Integrated Rural and Tribal Development (CIRTD) in Sundargarh district, Orissa, India.

Dokkeo Sayamoungkhoun and her fellow rice growers work with the EU-funded SRI-LMB programme, which is implemented across the Lower Mekong Basin.

Sabarmatee runs an SRI and organic farming research and training centre at Sambhav.